The first time I stepped foot in a gym, I wondered why it used 45 lb as the heaviest plate weight (some have a 100 lb plate, but those are not nearly as standard as the 45 lb plate). I would have expected it to be a 50 lb plate, to make calculations simpler.

The first explanation I thought of was the metric system: 45 lb is roughly the same as 20 kg. Well, 20 kg is much closer to 44 lb than 45, but it’s understandable to want to bump it 1 lb to make it a clean multiple of 5. However, if we’re being consistent in using the imperial weight that’s the closest multiple of 5 to its metric counterpart, we wouldn’t have a 25 lb weight. The equivalent of a 10 kg weight would be 20 lb, because 10 kg = 22.05 lb, which is closer to 20 than 25.

My next thought was that 45 lb plates might allow for different total weights to be achieved with fewer plates than a 50 lb would: Any 50 lb plate could just be replaced by two 25 lb plates, whereas 45 lb would require three plates (10, 10, 25) to replace, unless the gym had 35 lb plates. This is an important point: 35 lb plates exist, but aren’t a given; I’ve seen them at roughly half the gyms I’ve been to. Because of this, I will consider both possibilities in this post.

Over the years I became used to the existence of the 45 lb plate, but recently the thought popped back into my head and I decided to do some due diligence rather than just assuming the idea in the last paragraph was true. Interestingly enough, the data did not verify this belief. Instead, it showed that the 45 lb plate was a very poor choice to be used as the standard.

My analysis was simple: For each increment of 5 lb, figure out the set of weights that could achieve that total weight with the fewest plates. Any intermediate increment (e.g. 17.5 lb) can only be achieve by adding a 2.5 lb plate onto the proper set, since all the other plates are multiples of five and thus can’t span that gap. Therefore, it’s not important to consider these. I did this for a standard set, then for a modified set, which was the same as the standard, except the 45 lb plate was replaced with a different weight. As I said earlier, 35 lb plates aren’t always a given, so I did this analysis for two cases: {5, 10, 25, 35, [variable weight]}, and {5, 10, 25, [variable weight]}.

I should note a couple things here. First, this is the amount put on one side of a barbell or machine, not both sides combined. Second, this analysis equally values each total weight, so it is thus assuming that any weight under a chosen max weight will have an equal chance of being loaded up. This may not be true, but I don’t have any data to follow that suggests otherwise, and assuming everything is equally likely makes for fewer calculations. So, I can’t say that the conclusions of this analysis are guaranteed, but I have yet to see any quantitative evidence for the 45 lb plate, so that leaves the scoreboard at non-45 lb plate: 1, 45 lb plate: 0.

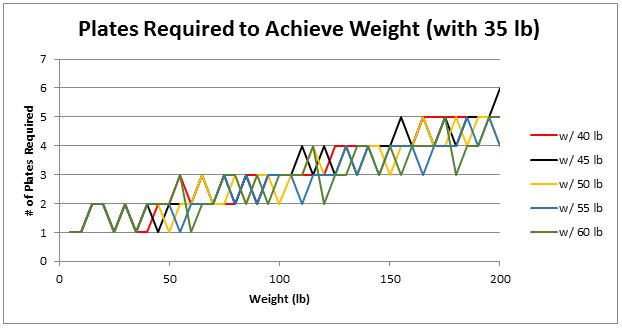

Alright, now let’s get back to the data. Here’s the graph of the number of plates required to achieve each weight for a set that includes a 35, with the heaviest plate being the one named in the chart legend. I graphed up to 200 lb, which some may find ridiculous to be loading on one side of a barbell, but the largest consumers of weight plates, gyms, should generally be able to expect that as a possibility.

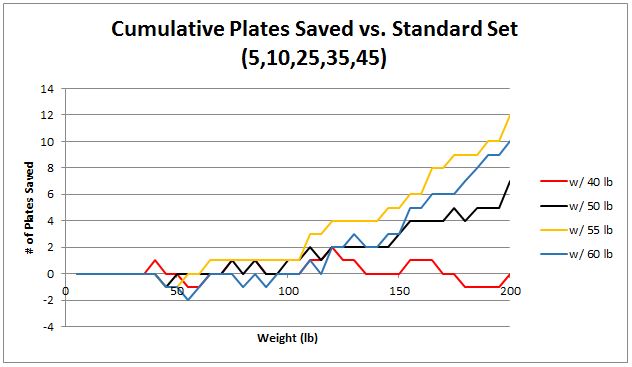

Ahh, now it all makes sense. Not really, this graph is hard to get anything useful out of, so I found a different way to look at it, which I called the Cumulative Plates Saved. At each total weight, I assigned each set a score, which was the difference between the number of plates required for the given set to achieve that weight and the number of plates required for the standard set. I made it so that a positive value is good (e.g. the {5, 10, 25, 35, 40} set requires 1 fewer plate to achieve 40 lb than the standard set, so it gets a score of 1). Then, for each given total weight, I would sum all the scores for weights less than or equal to that weight for the given set, hence “Cumulative.”

I know that was confusing, so if you have trouble following, here’s the value of this measurement: if you can pinpoint the highest weight you would conceivably put on one side of a barbell or machine, the set with the highest Cumulative Plates Saved at that total weight will save you the most plates used for all total weights less than or equal to your max weight. I did not include the standard set in this graph because it would, by definition, be a constant zero. Because of that, we can deduce that the only way the 45 lb plate can be preferable is if all of the other sets are negative at the desired max total weight. Let’s take a look:

Woah… I’ve got to say, this graph makes the answer for which plate is best way more obvious than I would have expected. As long as the max weight you foresee loading onto one side of a barbell is anywhere between 55 and 200 lb (corresponding to the entire bar weighing 155 to 445 lb), the 55 lb plate is your best option, or at least tied for your best option. Further, there is a significant range of max weights, between 95 and 175, where all four of these options are the same or better than 45 lb. Finally, just in case you haven’t gotten the point yet: there is not a single point on this graph where the standard set is better than all the rest. Not a single point.

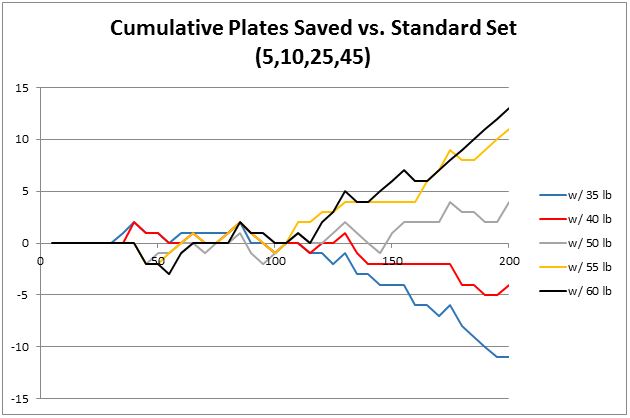

Now that we’re clear on sets that include 35 lb plates, let’s take a look at the case when there aren’t any 35 lb plates, and the 45 lb plate is again variable:

With the 35 lb plate taken out of play, the results aren’t much different, except that the 60 lb plate looks better than it did with the 35 lb plate in play. Once again, there is no point where the 45 lb plate is better than all of the rest. There isn’t as much of a clear winner here, but if your max weight is 80 lb or higher, either the 55 or 60 lb plate will be your best bet, or tied for your best bet.

Because of its strong performance regardless of whether there are 35 lb plates present, I would say that the 55 lb plate is what should be used as the heaviest weight in a set (anyone know if 55 Fitness is trademarked?).

Out of curiosity, I paired the winner of each case above if we were judging based on 200 lb being the maximum loading (a fair bet for a gym with some strong deadlifters), and found their Cumulative Plates Saved, both against the entire set, even though one of them is short a 35. Here’s the result:

What’s not surprising here is that the set with one more plate denomination allows for more saved plates, but what is surprising is that, if we assume we’ll be loading anywhere up to and including 200 lb, the set of {5,10,25,60} is better than the current standard set, which has one more plate denomination: {5,10,25,35,45}. Conclusion: planning could have served the weight lifting community well. Instead of non-uniformly mirroring the metric system with the 45 lb plate, they could have chosen two preferable courses of action:

1. Use a 55 or 60 lb plate to minimize the number of plates used. These two will beat the 45 lb plate as long as people can load up to 105 lb, regardless of whether there’s a 35 lb plate.

2. Use a 50 lb plate to make calculations easier, and most likely still reduce the number of plates used. Above that same 105 lb benchmark, the 50 lb plate will be preferable to 45 lb except for the specific case where the max weight loaded is 145 lb and 35 lb plates aren’t present. Even in that case, the trade off of one lost plate for easier multiples seems like a win to me.

Bonus thought of the day: Over the past 10-15 years, there was a silent move from two spaces after a period to one. Maybe I missed something, but I was taught two and was never told to switch; I just did so naturally when I noticed one becoming more common.

Write a comment

Adam Wang (Thursday, 23 April 2020 12:43)

Very, very strong work.

Re: Adam (Tuesday, 01 September 2020 19:42)

Just trying to flex my brain a bit.

-Kellen

John (Friday, 19 March 2021 19:41)

"what is surprising is that, if we assume we’ll be loading anywhere up to and including 200 lb, the set of {5,10,25,60} is better than the current standard set, which has one more plate denomination: {5,10,25,35,45}."

That's not really clear from your data. They're basically the same in the range you looked at, with {5, 10, 25, 35, 45} performing better under ~120 lbs. and {5, 10, 25, 60} performing better over.