As the days get hotter here in the Northern Hemisphere, I become more inclined to put ice in my morning coffee as an additional means of staying cool. Doing so this past week led me to realize an interesting point about putting ice into drinks that aren’t water: Initially, the more ice you put into the drink, the more watered down it gets, but after a certain maximum point, adding more ice actually makes your drink less watered down. In fact, theoretically, you could put enough ice in to not water your drink down at all.

To understand why this happens, we need to understand how ice cools our drinks down. There are actually three steps in the process, all of which require heat to move from the drink to the ice, thus cooling the drink down. The first step is heating the ice up to its melting point. The average freezer is approximately 0°F, and the melting point of ice is 32°F. Once the ice has reached 32°F, it then must melt, which also requires additional heat. This happens at a constant temperature, so once the melting is complete you have 32°F water. Assuming the drink is warmer than that, the water must then mix into the drink and warm up, further taking heat from the rest of the drink and cooling it until the two reach the same temperature.

For the purpose of this topic, we can lump everything that happens after the ice warms to 32°F together. This latter part of the drink cooling timeline is where most of the heat is taken from the drink, lowering its temperature. Knowing that, let’s graphically depict the heat an ice cube is able to extract from a drink. The image below shows the heat needed to warm an ice cube to 32°F in red, and the heat needed to melt it and warm the liquid in white:

An ice cube

Each square is some arbitrary but constant amount of heat the ice cube can consume. So if we have a drink that needs 9 squares of heat removed, we can achieve that by putting three ice cubes into it:

A cold cup of coffee

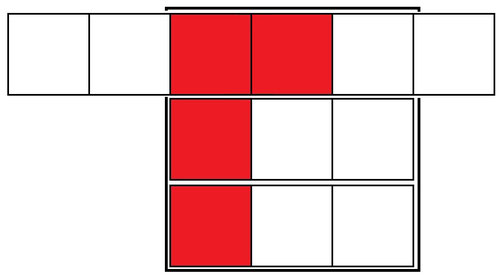

This does the job of cooling the drink down, but we end up with three ice cubes worth of water in the drink. If, alternatively, we only put 2 ice cubes in, we would have less water added, but of course we wouldn’t have cooled the drink down entirely, because we only would have stolen 6 squares of heat from the drink, not 9. I’m sure you know where this is going next: instead, we can add ice to the drink, to exceed the 9 necessary squares:

A cold, less watered down cup of coffee

By adding a fourth ice cube, we exceeded the cooling ability necessary, which means all the squares outside of the 3x3 square are unharnessed cooling ability. In other words, the white squares jutting out of the sides denote ice cubes failing to melt. So while we added another ice cube to the mix, there are three white squares outside the large square, which we can take to mean one and a half ice cubes that didn’t melt (2 white squares = 1 melted ice cube). Thus, only 2 and a half melted this time, rather than 3. If we added nine ice cubes, the entire large square could be filled with red squares, and thus not have any melting occur at all.

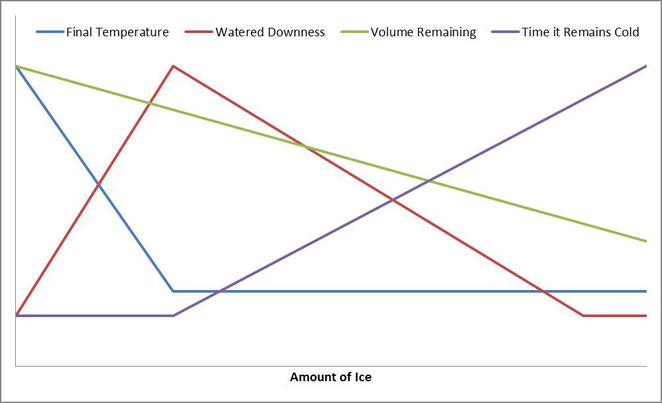

So we can see here that the point with the most ice cubes used while still having all the ice cubes melt gives you the most watered down drink, and adding less or more will improve your drink on the watered-downness front, but that’s not the only factor at play here. We also have final drink temperature, length of time the drink stays cold, and volume remaining for drink. The graph below shows how all four of these play out as ice is added, with the right being more ice.

For me, the optimal point is somewhere in the range of halfway to 75% of the way to the right. It’s obviously personal preference when it comes to which spot is better, but knowing the trends can help turn your watered down iced coffee to that of a pro in no time.

On a similar note, a month ago, when talking with a buddy of mine, he posed a question about whether it’s better or worse to leave a cold drink in front of a fan on a hot day. To the untrained mind, this may seem like a good idea, because it feels cooler to you when you’re in front of a fan (most of the time – more on that shortly). This is because the movement of the air allows for convection of heat, which happens much faster than conduction, which is how heat escapes the body in still air. So, if the air is cooler than your body temperature, then wind will cool you off faster. However, if the air is hotter than your body, the wind will actually speed up the heat transfer to your body rather than away from, and make you hotter. With humans’ body temperature being relatively high compared to average air temperature, this is uncommon and thus easily forgotten, but it can certainly happen in places like the southwest desert states of America. This same idea applies to the cold drink in front of a fan. The fan will speed up the heat transfer, but that heat will be from the hot air to the cooler drink, heating it up faster.

Write a comment