In my last post, I explained why widening roads isn’t a useful thing to do. I’d suggest reading that first if you haven’t, but the main takeaway was: in highly populated areas (where most people live), the amount of traffic will settle itself at the worst point where people still choose driving over alternatives, and thus is a function of human priority setting more than a function of road design. From here, I’m going to explain why I don’t expect autonomous cars to improve our lives.

I should note that I am writing specifically from a USA perspective. Handled properly, autonomous cars could be a great tool for improving lives. Unfortunately, the USA’s track record of obsessing over cars and treating workers poorly compared to other Western nations does nothing to convince me it will be able to realize this possibility. This is really at the heart of my stance on autonomous cars: they’re a technology that could do a lot of good, but human nature will most likely turn them into a net negative.

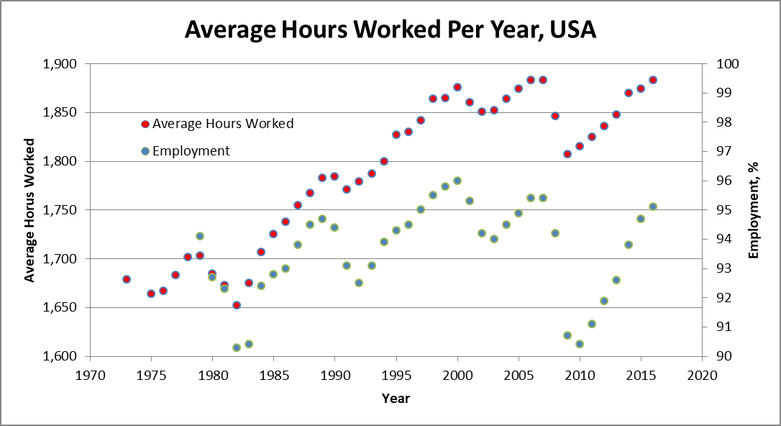

One of the big talking points among proponents of autonomous cars is that they will free up more time. Once the cars are truly autonomous, riders will no longer need to pay any attention to driving, and will thus be able to spend their commute time doing other things. This is a completely valid claim. However, in the USA, the trend over the past half century – a period that’s almost certainly seen more “time saving” innovations than the entirety of human history before then – has been that more time saved throughout the day means more time spent working. Here is a graph of average working hours per year for Americans in that time period, from the Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America Data Library. I included the employment percentage to show that the periods when average hours worked dropped were almost exclusively when fewer people were working at all. The key here is, beside the fluctuations both share, average hours worked trends up over time, while employment does not.

Is it really an improvement to replace time spent doing something most people don’t enjoy with time spent doing a different thing most people don’t enjoy? From a standpoint of further advancing our society, sure, that trade-off is an improvement since people working is more impactful to advancement than people driving is. However, I think a question that is seriously under-asked is “what is the point of this advancement?” The obvious answer is “to make our lives better,” which is a good answer, but far too simple. If our goal is really to improve lives, why are we working employees harder than before? That’s a direct contradiction. If our workforce was able to provide everyone’s needs in 1975 with an average of 1679 hours worked/person, why, in 2016, with a vastly more efficient workforce, did it require 1883 hours/person? This answer is simple: it didn’t. We need far fewer working hours per person to produce everyone’s needs now, thanks to widespread automation. The additional hours are spent on “advancement” – things that aren’t necessary or, in some cases, even beneficial – in hopes of “making things better”. It can be argued that some forms of advancement are necessary, but I doubt anyone would argue all advancement is necessary, e.g. better alternative energy sources may prove to be a requirement for human society to continue indefinitely, but wireless headphones certainly won’t. If we really wanted to make things better, we would actually take advantage of our advancements by requiring fewer working hours. We don’t need to scale it back to the point where no one works on “advancement”; we could still have that, and also provide a better life for people today, rather than an empty promise of a better life tomorrow. The reality is that we are “advancing” so that we can “advance” more, because “advancing” makes a select few people very wealthy. No one seems to question this, and I think it’s time we did – queue this post.

To tie that digression back in with the topic of autonomous cars: autonomous cars may save riders some time, but this will likely come with a creeping increase of expected time spent working. Ultimately, I would classify this more as a neutral or slightly positive effect than a negative one – but still not an overwhelmingly positive one. My other expectations are less favorable, however.

To call upon part 1 of this post, the idea of Personal Cumulative Cost (PCC) is useful in reasoning about the impact autonomous cars have. To recap the idea, it’s the total cost (money, time, pleasure, etc.) of a place to live and all the changes that come with it. Autonomous cars will impact people’s PCC equation, and I don’t think the results will be good.

The commuting portion of PCC has two main parts: time and money. To some, stress/wellbeing is also involved, but is likely a smaller portion. Autonomous cars will reduce the commute portion of PCC for the same commute by partially or completely removing the time cost. This may sound contradictory after my last point, but notice that I never actually denied that autonomous cars will save time by allowing riders to point their attention elsewhere. My claim was that this time will be offset by work hours, which wouldn’t factor into PCC, as it’d become expected regardless of your commute.

So, the question now is: what would be the impact of reducing the commute portion of peoples’ PCC? The short answer is that people will live farther away from work & other places they often commute to. Many predict that autonomous cars will reduce traffic since the computers operating the cars would follow more predictable and synchronized patterns than humans ever could. This very well may be true, but let’s look at it in comparison to the previous post.

Widening roads will, in the short term, reduce traffic, which reduces the commute portion of many peoples’ PCC equation, making people more willing to drive on that road, until the commute times resettle at the point people find acceptable – which doesn’t depend much on road width. Here, we’re keeping the road the same, but again reducing the commute portion of peoples’ PCC equations by both speeding it up (reducing traffic) and making the time component less significant because that time isn’t wasted as much as when actively driving.

Let’s give autonomous cars the benefit of the doubt here and assume their traffic reduction is infinitely scalable – no traffic delays no matter how many cars there are on the road. In that case, the main driver of induced demand from the previous post – people moving – won’t actually impact others’ commute times, thus making the commuting portion of the PCC permanently lower, per mile, than it was before. This means people will be willing to live farther away and commute more. Note: if we don't assume infinite scalability, that would diminish the following effects, but it would also diminish the whole "it'll reduce traffic" argument proponents use.

So what if people live farther away from work or other regular destinations? Well, for starters, until cars run on 100% renewably-sourced electricity, there will always be negative environmental consequences of more car use. Additionally, this would lead to more sprawling, suburb-heavy, urban areas rather than densely populated ones. Los Angeles is the obvious case study for this – it boomed around the time cars were becoming ubiquitous in the US, and has embraced cars as part of its culture. It’s no coincidence, then, that Los Angeles County grew to be basically the definition of sprawl today. Sprawl is once again an environmental concern, for a few reasons. First, it means more natural habitats destroyed, and second, living in dense cities is in general more environmentally friendly than sprawling suburbs for many reasons: Less energy is needed to heat/cool a small apartment than a house, common commuting options are greener in cities, and less infrastructure and logistics are required to get goods and utilities to people. Basically, it takes more energy to “connect the dots” (dwelling, store, work, water/electricity plants, etc.) if the dots are far apart, and autonomous cars will likely make the dots farther apart.

Aside from environmental concerns, there’s human wellness concern here as well. This study found that people are healthier when they live in densely populated cities than they are in suburbs. This largely is due to the point I made above, of greener commuting options in cities. Greener commuting options are greener because they rely on human power (walking, biking, etc.), and that also means they’re built-in exercise in peoples’ daily lives.

Thus far, the points I’ve made have been extrapolations of things that have already happened, to a post-autonomous car world. This makes them easier to defend with research. My final point is more speculative, but I feel it’s worth sharing as food for thought:

I expect the “spreading out” of people resulting from autonomous cars to increase socioeconomic segregation. Poorer people naturally have less mobility than wealthier people – many can’t afford a car in the first place, or have fewer options of potential places to move to that they can afford. Therefore, the wealthier people will be the first to spread out, so the areas that boom from this will consist mostly of wealthier people. Also, even among those wealthier people (which contains a fairly large range, I’m not talking about just the top 1% or even 10%), subdivisions by wealth will likely be even more prominent than they are now. People generally seem to like living near people of similar wealth to them – which is really just a way of saying people like to live in the “nicest” (translation: most expensive) neighborhood they can afford. This and commute are two large factors in most peoples’ decisions on where to live, and by making the commute portion smaller, “living among equal-wealth peers” plays a larger relative role.

Some may not see this as a problem, but I definitely do. Segregating people in this way leads to more tribalism, which, in my humble opinion, is one of the human race’s largest issues. The internet and social media have already caused a spike in tribalism by making it easier for people to find, and limit their interaction to, like-minded people. I’m certainly a fan of finding like-minded people, but I think it’s crucial to also get exposure to a diversity of backgrounds and thought for better perspective. People forming cliques of roughly-equal wealth will make it easier for the wealthy to forget about the impoverished and how they need help – out of sight, out of mind.

The wealthy people also support shops and restaurants, since they have more disposable income, and they will thus take service jobs with them when they spread out. This would leave the poorer people with fewer jobs, which could cause inner cities to decline like they did in the USA’s original suburb migration. We might as well throw in the loss of one of the USA’s more common jobs, truck driver, to autonomous trucks as well. All of this would likely increase income inequality, which is already a problem in this country. Income inequality is bad for everyone, even the wealthy, because it slows the economy as a whole. To make matters worse, the “out of sight, out of mind” point from the last paragraph would make it harder to pass the necessary legislation to mend income inequality, since people wouldn’t see it as much in their day-to-day lives, and thus would be less likely to think it’s important.

On the surface level, autonomous cars will be great: less traffic, fewer accidents, not as wasteful of commuting time. Most people who talk about them stop there, but that doesn’t give you the whole picture. When thinking about any change, it’s important to consider the immediate impacts, as well as the secondary impacts that result from the immediate ones. Otherwise, you’re not getting the whole picture. In the case of autonomous cars, those secondary impacts are all a result of how human nature leads us to change our lives in response to autonomous cars, and everything I’ve learned thus far about human nature makes me believe that the overall impact of autonomous cars will be a negative one. However, for individual people, you can reduce the downsides by not falling into the trap of becoming complacent with longer commutes as a result.

Write a comment